15 Clunky Phrases to Eliminate From Your Writing Today…and How to Crack Down on Wordiness

At one time or another during our years in education, we’ve probably all been handed a homework assignment with an impossible-looking word count that’s forced us to think of creative ways of attaining the requisite number of words without actually having to say anything extra.

You should also read…

This problem often leads to clunky phrases, with unnecessary additional words used as a filler to help reach the word count more quickly; these words and phrases are usually redundant, read poorly, or take five words to say what could be said in one. Another factor behind clunky phrasing is the need to sound more intellectual; many students labour under the misapprehension that lengthening their sentences, and making their writing sound more complicated by using more verbose words and phrases, will make their writing appear more learned. It’s not the case, of course; it simply makes the essay harder to read, which defeats the object: a good essay should explain things clearly and be enjoyable to read.

To improve your academic English, you’ll need to get out of this habit and start being more economical with your words. In this article, we’re going to show you a few specific phrases that can be shortened or altered to make them more elegant. If word counts are an issue, you’ll find a section at the end of this article discussing other ways of reaching the prescribed word count.

Common clunky phrases

Let’s start by looking at some of the most commonly used clunky phrases. This is by no means an exhaustive list, but once you’ve grasped why this lot degrade the quality of your writing, you should have a good idea of what else to avoid.

1. In terms of

“In terms of” is a meaningless phrase often employed in speech, but it’s also popular with students who perhaps think that it makes their writing sound more academic by adding emphasis. “In terms of Bronte’s imagery, the author has some interesting observations.” A better way of phrasing this would be to turn it around and change the “in terms of” to “about”: “The author has some interesting observations about Bronte’s imagery.” It’s almost always better simply to use a single preposition in place of this phrase. For example, “the data is expressed in terms of a percentage” could easily be rephrased to “the data is expressed as a percentage”.

2. The fact that

Phrases that incorporate “the fact that” can virtually always be simplified. For example, “due to the fact that” can be changed to “because” or “since”, and so can “in light of the fact that”; “given the fact that” can be replaced with “since”.

3. Needless to say

This phrase, in common with “it goes without saying”, means “it is assumed”, that something is self-evident, or “it doesn’t need to be said”. The clue here is in the meaning: “needless to say” doesn’t need to be said, as the sentence will work perfectly well without it.

4. In order to

In most cases, the phrase “in order to” works just as well without the “in order”, with the infinitive form of the verb on its own. For example, the phrase, “In order to assess the author’s intentions” would work just as well if it read, “To assess the author’s intentions”, and no unnecessary words will have been used.

5. All of the

Many people make the mistake of adding the “of” after the word “all”, as in “I finished all of the cakes”. This doesn’t just sound clunky – it’s wrong. The “of” is only necessary when the word following it is a pronoun, as in “all of us” or “all of them”. When the next word is “the”, the “of” is dropped, so the aforementioned example becomes “I finished all the cakes”.

6. At the end of the day

“At the end of the day” is an idiom, and it’s therefore less appropriate to use in an academic essay anyway; but if you do find yourself thinking of using it, remember that this phrase takes six words to say what could be said in one: “ultimately”.

7. First and foremost

A common phrase to read in student essays is “first and foremost”, as in “First and foremost, we need to look at the evidence.” Since “first” and “foremost” mean the same thing, it’s unnecessary to say both: “Firstly” would suffice. If you’re tempted to write “first of all”, it’s also advisable to substitute it for “firstly”.

8. The passive voice

Though this is not itself a clunky phrase, its use is responsible for many a clunky sentence. Students often employ the passive voice when writing essays because they think it makes their writing look more intellectual. In fact, it makes it harder to read and less interesting than using the active voice, and usually adds unnecessarily to the word count. For the difference between the two, have a look at the following examples:

Passive: It was decided by the authorities that a curfew should be imposed.

Active: The authorities decided to impose a curfew.

Rephrasing this from the passive voice to the active has reduced this phrase from twelve words to seven, and made it sound more interesting in the process.

9. Expressing possession

Another clunky wording arising from the complexities of English grammar is the use of the possessive, or the idea of something belonging to someone or something else. Rather than saying, for example, “the core of the Earth”, you could say “the Earth’s core”, which would sound neater.

10. It is important to note that

This is a fairly meaningless expression, the sentiment of which could be equally well expressed by saying “Importantly” or by leaving it out entirely. For example, “It is important to note that not all scholars agree on this” could be changed to “Not all scholars agree on this.”

The second version works just as well without the clunky phrase that starts the first version, and it’s a much neater way of expressing the same thing.

11. In actual fact

Just say “actually”, or don’t use it at all.

12. Inasmuch as

“Because” or “since” are much better ways of saying this.

13. In excess of

This is a pompous way of saying “over” or “more than”. For example, instead of saying, “The site was occupied by in excess of a hundred people”, it would be better to say, “The site was occupied by over a hundred people.”

14. In the process of

This phrase is usually redundant, meaning that the sentence works without it. For example, “When you’re in the process of gathering data…” becomes “When you’re gathering data”.

15. Whether or not

It’s usually preferable simply to say “whether”. For instance, “The character had no idea whether or not she would be making the right choice” would become “The character had no idea whether she would be making the right choice”.

Tips for writing more concisely

We’ve now seen some of the most frequently used clunky phrases, which should enable you to spot others in the same vein. Some more general tips on writing concisely may also come in useful, as these will help you combat the issues that lead to wordy, inelegant phrasing and help you edit them out before your essay reaches your teacher. Here are our top tips.

- Ask yourself what you’re trying to say. Being clear in your thinking is a big step towards achieving clarity in your writing; if you aren’t sure what you want to say, waffling is almost inevitable.

- Read your writing aloud and see how easy you find it. If you find yourself stumbling over your words, or having to start a sentence again, you may need to edit to make it more concise and easier to read.

- If you read your work aloud and it sounds far more complicated than it would do if you were simply explaining something out loud to a friend, it needs simplifying. When you write, imagine that you’re talking to a friend. That doesn’t mean employing conversational English, of course; stick with a formal tone, but try to explain the concept as clearly and simply as you can, eliminating unnecessary words that you wouldn’t use if you were speaking.

- Re-read the sentence and cross out any words that don’t add anything to the meaning (such as “basically” or “actually”). This will help you distil the sentence to the bits that matter.

- Use words instead of phrases where possible.

- Weed out unnecessary repetition (“9am in the morning”, for instance, should just be “9am” because the “am” bit tells you that it’s in the morning).

- Use the “Ctrl + F” function on your word processor to take you straight to instances of the phrases we’ve discussed in this article. This will help you fix glaring clunkiness quickly.

And if you’re struggling with word counts…

At the beginning of this article, we talked about students’ difficulty reaching word counts as being one of the major causes of clunky phrases and filler words. If you’re having trouble writing a long enough essay, you don’t need to sacrifice neat, concise writing just so that you can squeeze in as many words as possible. Here are some other ways in which you can up the word count instead of using phrases like those outlined above.

Introduction and conclusion

Clearly, the introduction and conclusion are vital components of a good essay, but they also bolster your word count. If you’ve started writing your essay by writing the ‘body’ of it first – constructing the points and argument – don’t forget that the introduction and conclusion will add to the word count if you feel you’ve run out of things to say. While neither should be too lengthy, this is an opportunity to add information on why it’s important to think about the topic you’re discussing, to summarise the arguments you’ve discussed, and to give your own opinion.

Define

Another way of boosting the word count of your essays is to define concepts as you go along. Even though you’re writing an essay for someone who knows a lot more about the subject than you, it’s a good idea to pretend that you’re writing for someone who doesn’t know the subject. This means defining concepts the first time you mention them, as this shows the person marking your essay that you have a firm grasp of what you’re writing about. In some instances, a definition may be particularly important because there may not be one agreed definition; in such cases, it’s best to acknowledge the lack of a widely agreed definition, giving a flavour of how definitions differ, and stating the definition you’ll be using in your essay to avoid any confusion.

Add background and context

If you feel that there isn’t enough you can say about the issue itself, you could add to the word count by explaining the background and context of the issue. For instance, an outline of the Industrial Revolution and its background would not look amiss in a discussion of certain William Blake poems, as this was going on at the time Blake was writing and had a profound influence on his poetry. The bonus is that you’ll also score extra marks for including context.

Quote other opinions

While you should be wary of quoting extensively from other works, it’s fine to quote a little or to paraphrase the scholars you mention. If you run out of things to say, you simply find another scholar who’s voiced an opinion on the issue and write about what they have to say on the subject.

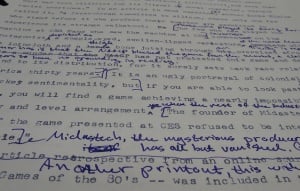

Once you get to university, you’ll probably find that you have the opposite problem with word counts, at least with a big piece of work such as a dissertation: you’ll end up having to shorten a piece to keep it within the word count, rather than worrying about reaching it. Hopefully the tips in this article will help you do this too. Why not print this article and put it up next to your desk to remind yourself what to avoid writing in your essays?

Image credits: banner; Jane Eyre; knitting; cupcakes; chickens; dog; crowd; editing; typewriter; Blake.